By Laura Holt

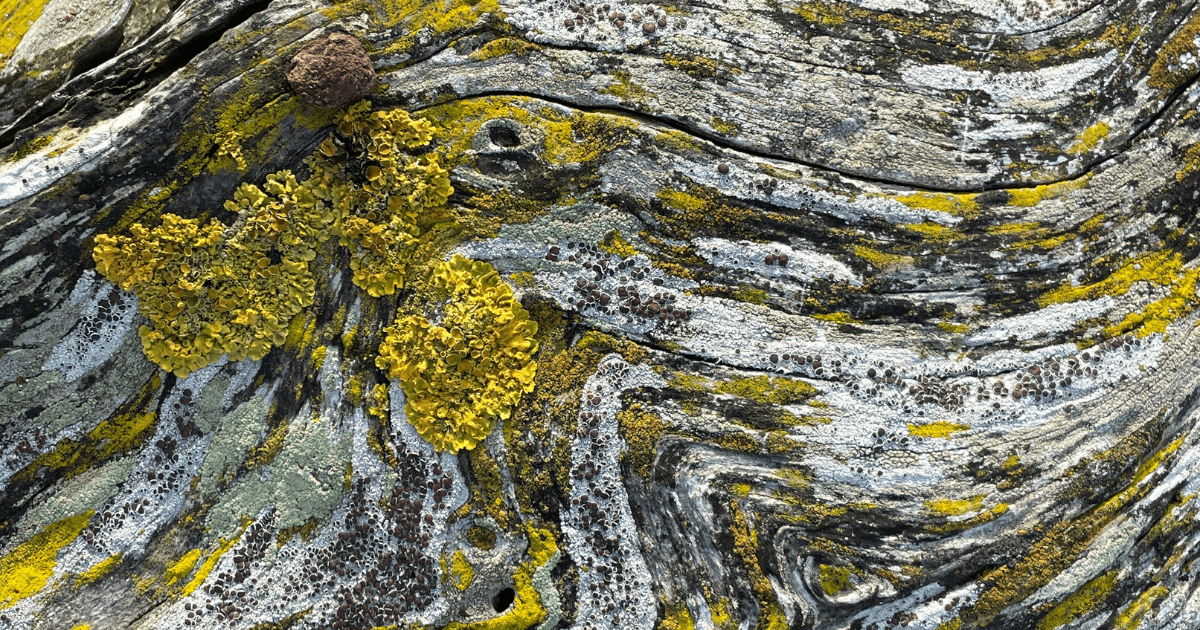

Over the past year I’ve found myself forming an appreciation and fascination for lichens. Initially, I noticed how beautiful and visually interesting they can be. I began photographing the colourful patterns made by crust lichens on rocks or the spectacular beard lichens (Usnea) draped from trees like a particularly fuzzy and soft green curtain. Once my interest was piqued, I started to come across snippets of information about lichens and their biology. As it turns out, lichens are equally fascinating as they are beautiful. What follows is a short introduction to the world of lichens and what I’ve learned so far.

So, what are lichens? Lichens are not a single organism, like plants, as I had always assumed to be the case. Instead, they are made up of fungi in combination with a photobiont, either green algae and/or cyanobacteria. Together, these organisms form the symbiotic relationship known as a lichen. The algae or bacteria is the partner responsible for photosynthesis, using sunlight to produce food for itself and the fungi. Meanwhile, the fungal partner creates the structure, enabling the lichen to grow in forms suited to its environment, as well as producing chemical deterrents to threats like herbivory.

Left: Orange coloured chocolate chip lichen (Solorina crocea) in Stagleap Provincial Park, B.C. Right: Common script lichen (Graphis scripta), found on a vine maple at the NTBC conservation area, Harrison Chehalis. With distinct squiggly markings, this small crust lichen is easy to identify once you start looking for it!

If the idea of lichens as a symbiosis isn’t intriguing enough, I am compelled by the idea that lichens are greater than the sum of their parts. The shape and function of the two partners (either fungi and algae or fungi and cyanobacteria) are transformed in these symbiotic relationships. Often the partners have co-evolved for so long that they are no longer commonly found growing alone. What I find most interesting is that as lichens, the fungi and photobiont can grow in habitats that are more extreme than either could tolerate on their own. Lichens are found in some of the most extreme conditions on earth and thrive in places like the arctic tundra and in dry deserts.

Lung lichens on Vancouver Island, B.C. Left is Lobaria oregana, and right is Lobaria pulmonaria.

So how are lichens named if they are made up of multiple species? Lichens are taxonomically organized around their fungal partner because in the world of lichens, fungi make up the most speciose group. For example, the same photobiont partner is found in many different lichens. There are only around 100 known species of green algae or cyanobacteria that form a symbiosis with fungi, in contrast to the 18,000 known species of lichenized fungi. Sometimes, this can even be seen from the colour of the lichen, where different types of algae will show up as a specific colour on the lichen’s surface. It is also possible for an individual lichen to include a fungi and multiple photosynthetic partners, where there is an algae as well as a cyanobacteria that are both photobionts!

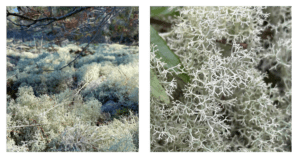

Reindeer lichen (pictured above) are a handful of similar-looking species in the genus Cladonia. These are best identified with chemical tests.

Lichens are generally very sensitive to their environments. Unlike plants, lichens are mostly made of nutrients obtained from the atmosphere. This applies especially to those that are epiphytic, living high up on plants where there are little other avenues to obtain nutrients. This also means that they absorb contaminants from the atmosphere, and over time these can become concentrated and disrupt the physical processes they depend on. Many lichen species are quite vulnerable to habitat disturbance or degradation, including from air pollution and climate change.

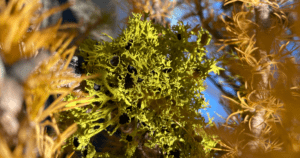

Brown-eyed wolf lichen (Letharia columbiana) at Manning Park, B.C.

This environmental sensitivity makes some lichen species a good indicator of air quality. Different lichen species have different sensitivities to specific pollutants so the presence or absence of lichens can then be used as an indicator of these pollutants, like acid rain or fluoride emissions. You can even see this play out in everyday life if you compare the lichens you see on street trees to the lichen species found in a forest outside of the city. In more extensive studies, the pollutants accumulated in a lichen itself are analyzed to get a picture of what pollutants are in the atmosphere.

Coral lichens (genus Sphaerophorus) on Vancouver Island, B.C. The photo on the right is Sphaerophorus tuckermanii, distinguished by its smooth surface.

There is much more to explore about lichens, and I look forward to seeing what I learn next. In my experience lichens often go unnoticed, as tends to be the case for small things, and I regret to say that I have not paid them much attention for most of my life. Stopping to look at the lichens has been a wonderful addition to strolls around a park, hikes up a mountain, or anything in between. Once I started to look for them, it turns out they are all around us, growing with beautiful diversity and living their own fascinating lives.

By Laura Holt, South Coast Conservation Crew Lead

By Laura Holt, South Coast Conservation Crew Lead