Ron Erickson’s recollections of the early days of The Nature Trust of British Columbia are filled with powerful stories: how a Red-tailed Hawk helped seal the deal on a million dollar donation, how synchronicity played a role in his becoming the Executive Director of The Nature Trust, and how a book about building an ark helped him launch an innovative approach to land acquisition.

In 1984 when Ron joined The Nature Trust of BC he had spent several years working as an environmental consultant in the province. A childhood in Salmon Arm where he enjoyed hunting and fishing set the stage for his interest in conservation, leading him to pursue degrees from the Faculty of Agriculture at UBC and Oregon State University.

Over the next 17 years he played a key role in taking the organization into a new era in conservation. Now retired, Ron took time out from his world travels to share highlights from those transformative years in The Nature Trust’s growth from 1984 to 2001.

Burt Hoffmeister with Ron Erickson and Gopher Snake

What stands out for you about your early days at The Nature Trust of BC?

Working with Bert Hoffmeister, Chair of The Nature Trust Board and Second World War hero. He was both remarkable and dynamic and such a powerful personality and a brilliant leader. In addition, two of my professors at UBC, Dr. Bert Brink and Dr. McTaggart Cowan, were on the Board and I thought I wouldn’t make many wrong decisions with those two brilliant advisors. Dr. Brink actually opened the door for me to be considered for the job at The Nature Trust.

What were some of the challenges you faced?

Balancing good projects while staying within our budget was always a challenge. A second challenge was establishing priorities. We couldn’t buy everything so we needed to focus our efforts.

The book Building an Ark – Tools for the Preservation of Natural Diversity helped me find a way to do that. The author, Phillip M. Hoose, described a method of establishing priorities in land conservation used by the Natural Heritage Program of the U.S. Nature Conservancy in Tacoma, Washington. I introduced the idea to two BC government biologists who were also enthusiastic about the approach. Together with the book’s author we drafted a proposal to raise funds for a program that focussed on gathering data to prioritize land acquisition and protection, currently called the BC Conservation Data Centre.

Former Board member Rod Silver and Ron Erickson on the summit of Mount Mary Henry

You spearheaded many innovations during your tenure. Are there any you’re particularly proud of?

The South Okanagan Similkameen Conservation Program is one I’m proud of because it’s in an area that includes a number of rare and endangered species.

When I was at Oregon State University, I was influenced by the book Design with Nature by Ian L. McHarg, which describes a process of sorting data to focus on where you should spend your efforts. With the encouragement of Dr. Brink and Dr. McTaggart Cowan I approached the Royal BC Museum in Victoria which had a lot of data on the flora and fauna in the province. My idea was to get as many scientists and technical people in BC to summarize what their research revealed about the rare and endangered species in the South Okanagan. I got amazing support from Dr. Rob Cannings, Museum curator, Dick and Syd Cannings, and Dr. Geoffrey Scudder, Professor Emeritus Zoology, UBC (and past board member of The Nature Trust) as well as regional biologists.

We brought everyone together at workshops at UBC and Penticton. The scientists came with all the information they had on many rare and endangered species including insects. Some of the species had never been identified before anywhere in the world. We created three maps of the South Okanagan showing the concentrations of the most rare and endangered species and their habitats. The most significant areas we identified were: the Vaseux Lake and White Lake area, the Okanagan River corridor between Okanagan Falls and Osoyoos Lake, and the area southeast of Osoyoos Lake.

With this information we started buying properties on the east side of Vaseux Lake. Then we started looking at ranches.

Vaseux Lake

Why was The Nature Trust interested in ranches?

We were interested in working with ranchers to look at ways of managing their land that was viable and conservation minded. That included caring for the wetlands and using a rotating grazing regimen to give the grasslands a rest in different seasons, reduce weeds and increase productive plants. The result was a big difference in the amount of forage production. We called them biodiversity ranches.

We bought three: Long Ranch at the south end of Skaha Lake, White Lake Ranch and Thomas Ranch, and we put together a plan to run them. We wanted to keep these ranches in place and viable so that the ranchers could make a living rather than selling them off lot by lot for more intensive development.

Were there other collaborations that made a difference to conservation efforts at the time?

Yes. Peter Jones of Ducks Unlimited Canada brought forward the idea of teaming up with The Nature Trust and Wildlife Habitat Canada to fund the purchase of estuary properties we thought were critical. Of particular concern were some 400 estuaries of biological significance along the BC coast which were threatened by marinas, log booming and so forth. This led to the creation of the Pacific Estuary Conservation Program. Representatives from the BC government also participated in the program. We focussed on estuaries where we could buy land to protect the inter-tidal areas for years to come.

The estuary program also started the idea of a group getting together to focus efforts and energies on specific projects. In recognition of our teamwork conserving estuaries we were awarded the Ramsar Wetland Convention Award for partnerships between non-governmental and governmental organizations to conserve wetlands of international importance.

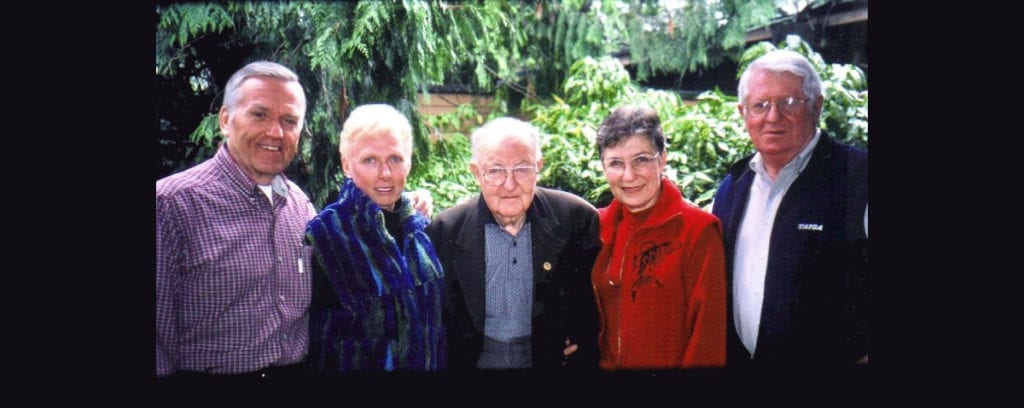

Ron Erickson with wife Jennifer, former Nature Trust Director Dr. Bert Brink, former Provincial Minister of the Environment Joan Sawicki, and Gary Runka

Was getting funding for these projects a challenge?

The Nature Trust of BC is a non-governmental organization so funding is always a challenge. Our volunteer board took a leadership role in all these projects including field trips with conservation groups to keep up the momentum.

One field trip I will always remember was with an individual who was thinking about making a significant donation but wanted to have a first-hand look at the property we were hoping to purchase. So we took a field trip together to the Thomas Ranch (now known as the Okanagan Falls Biodiversity Ranch). As we walked the property we stopped to look over a beautiful view and at that moment a Red-tailed Hawk swooped low overhead. It was a dramatic sight and I believe it helped him make the decision to donate over a million dollars to help buy the property.

Did your more scientific approach make a difference to your conservation strategy?

Yes. It facilitated the acquisition process with other conservation groups. We could build a business case using scientific tools. Whether it was the Cowichan River estuary or a property like the Okanagan Falls Biodiversity Ranch we could say this is how it fits in with our conservation strategy and these are the benefits.

Looking back, is there a highlight of your time with The Nature Trust of BC?

One of the highlights for me was meeting the people on the original board – meeting someone like Bert Hoffmeister, who I worked with virtually every day for more than six years. He was a hero. And working with The Nature Trust’s first accountant, Ed Moul, who went on to become Chair, was also a milestone for me. I never had a boring day. It was always exciting because there were always several projects on the go at the same time.

Looking ahead, what do you see as some of the challenges and opportunities for The Nature Trust of BC?

The Nature Trust is focussing on the right properties and it’s doing it efficiently. But, The Nature Trust has always been short on promoting itself in the province. It’s a fantastic organization that more people need to know about.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.