As urban areas and agriculture continue to expand throughout British Columbia and the rest of the world, the loss of natural habitat has increasingly put pressure on wildlife – reducing biodiversity in everything from insects and mammals to birds and amphibians. But something that is often overlooked is how human development not only removes habitat, but also fragments the habitats that are left. Habitat fragmentation, the process by which large and continuous habitats get divided into small and isolated patches, is now considered one of the greatest threats to biodiversity.

Imagine you are a small Nuttall’s Cottontail rabbit living in a large, healthy grassland with plenty of access to all of your habitat needs. But one day, a major road is constructed right through the middle of your grassland. This road becomes a barrier to movement and trying to cross it could be lethal. The grassland on the other side of the road becomes inaccessible. Now, you can only breed with other rabbits on your side of the road, which can put your population at risk of inbreeding. If disease, or some other natural catastrophe strikes, the rabbits on your side of the road could become locally extinct.

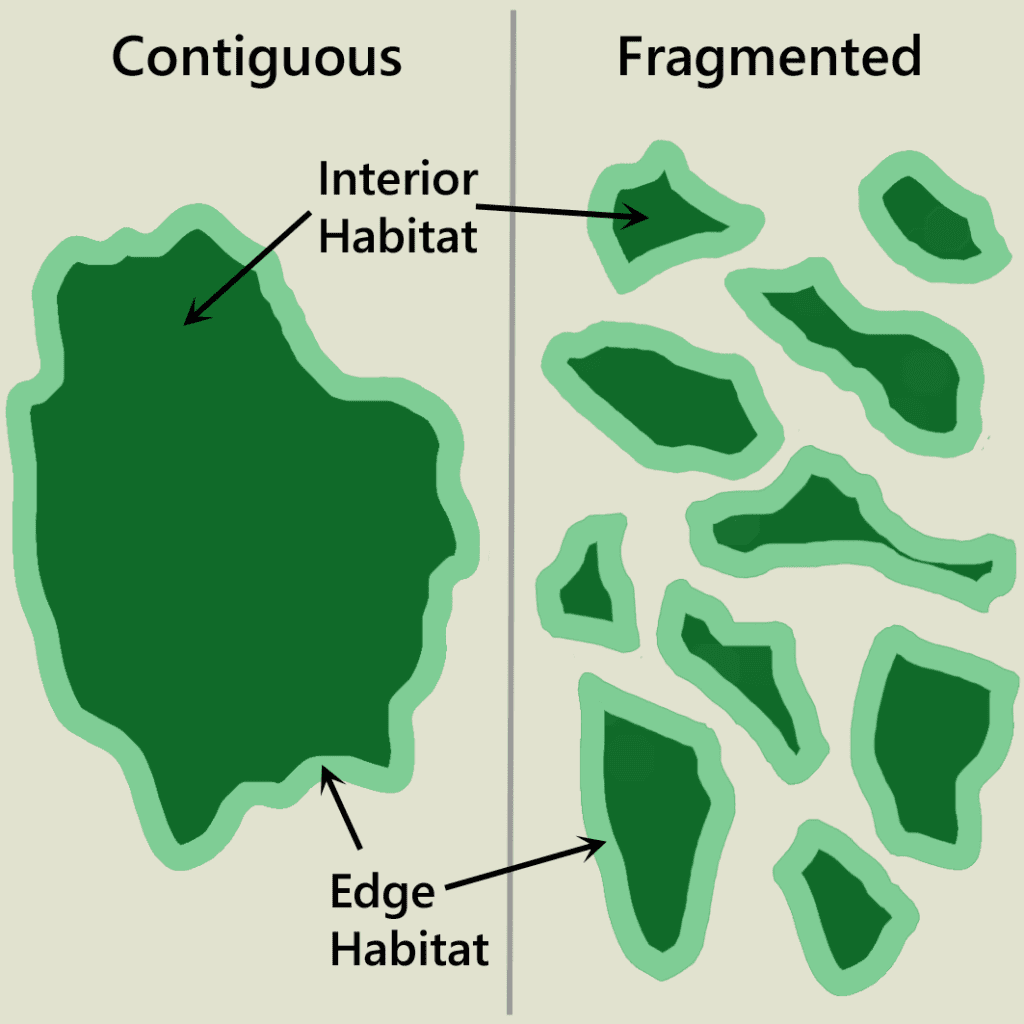

When developments happen on a landscape, they create a barrier that prevents wildlife from moving freely from one part of their habitat to another. As habitats become chopped up into smaller and smaller fragments, they become like “islands” – exposing species to threats within their habitat, but also when they attempt to venture to new areas. Fragmentation also leads to increased “edge effects”, which are the negative consequences of having more edge areas exposed to adjacent development compared to protected interior habitat. This allows for things like increased road mortality, invasive species presence, disease, human-wildlife conflict, genetic inbreeding, and harsh weather exposure.

When developments happen on a landscape, they create a barrier that prevents wildlife from moving freely from one part of their habitat to another. As habitats become chopped up into smaller and smaller fragments, they become like “islands” – exposing species to threats within their habitat, but also when they attempt to venture to new areas. Fragmentation also leads to increased “edge effects”, which are the negative consequences of having more edge areas exposed to adjacent development compared to protected interior habitat. This allows for things like increased road mortality, invasive species presence, disease, human-wildlife conflict, genetic inbreeding, and harsh weather exposure.

Not all species are impacted equally by habitat fragmentation. For example, species that are sedentary and cannot move very far are affected only if their specific area is lost. On the other hand, species that disperse and move around are affected by the total amount of connected habitats available. Larger mammals like bears, wolves, and cougars require vast amounts of habitat to feed themselves, reproduce, and carry out their lives. Therefore, these species are often most at risk when habitats become severely fragmented.

As climate change continues to alter habitats, it is especially important that we provide species with the ability to adapt as best as they can by providing lots of connected habitats. Allowing wildlife to move northward or to higher elevations will all help reduce the threat that rising temperatures from climate change will have on countless species. Thankfully, conservation organizations like The Nature Trust of BC are working to protect areas that connect habitat fragments, ensuring species can move more freely throughout the landscape. You will often see The Nature Trust of BC purchasing multiple tracts of land that are adjacent to one another. This way, as few barriers as possible are impeding wildlife movement, giving them a better chance to thrive in our beautiful province!

Sources:

1. Bright, P.W. 1993.Habitat fragmentation – problems and predictions for British Mammals.

Mammal Review 23:101-112.

2. Wilson, M. C., X. Chen, R. T. Corlett, and R. Didham. 2016. Habitat fragmentation and

biodiversity conservation: key findings and future challenges. Landscape Ecology 31:219-227.

3. Henden, J., R. A. Ims, N. G. Yoccoz, and S. T. Killengreen. 2011. Declining willow ptarmigan

populations: The role of habitat structure and community dynamics. Basic and Applied Ecology 12:413-422.