The Nanaimo River Estuary is the largest estuary on Vancouver Island and is rich in natural resources. It’s utilized by five of the Pacific Salmon species and various other wildlife, including Black-tailed Deer and American Black Bear. Birds are also abundant in the estuary, with over of 200 species having been observed in the estuary.

The Nanaimo River and the associated estuary are both located on the traditional territory of the Snuneymuxw First Nation (SFN), who have sustainably harvested fish, shellfish, plants, and other foods and resources from the estuary for thousands of years. However, European settlement in the region introduced industrial activity and agricultural practices that disrupted the natural processes of the estuary and river, including tidal connectivity of the upper saltmarsh, deposition of gravel into the river, and changes to freshwater flow and distribution.

Lesser Yellowlegs foraging along the Nanaimo River

Over the last few years, The Nature Trust of BC (NTBC) and our partners at SFN and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), have invested significant effort and resources into removing and restoring some of the historic anthropogenic features and industrial land uses that have degraded the estuarine ecosystem, with approximately three kilometres of agriculture berms removed, reconnection of tidal channels, and planting thousands of native plants to improve fish and wildlife habitat.

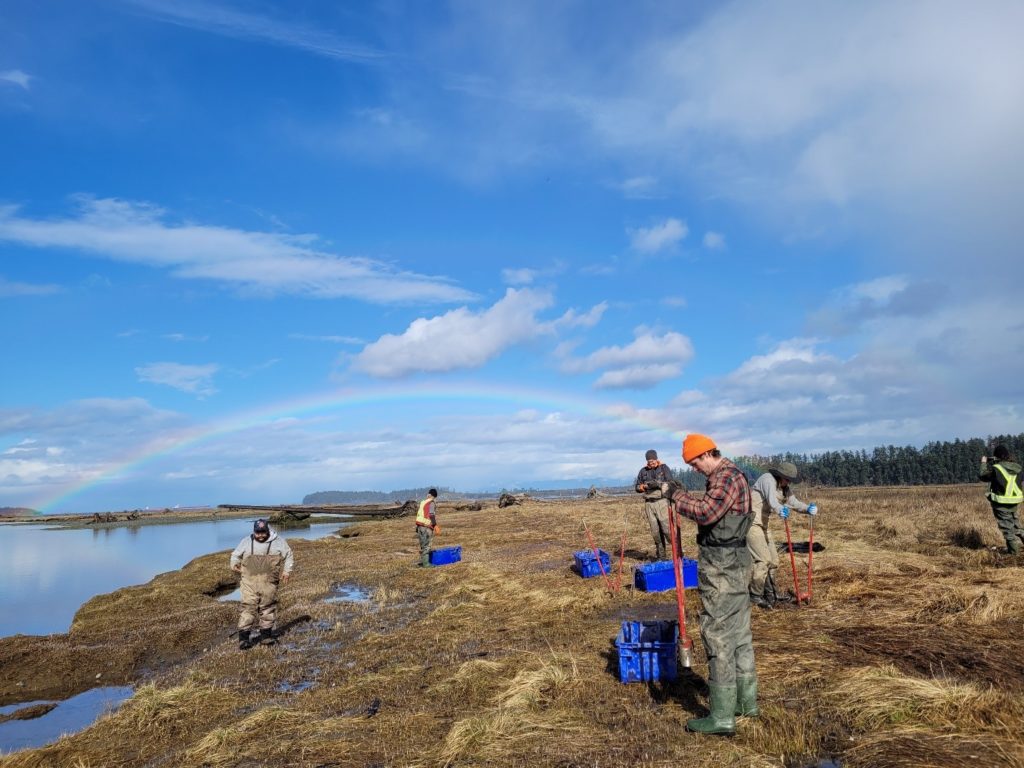

NTBC and SFN staff collecting Lyngbye’s Sedge (Carex lyngbyei) for transplanting at one of our restoration sites in the Nanaimo River Estuary

After our first three years of monitoring through our Enhancing Estuary Resiliency project, the Nanaimo River Estuary was identified as a top candidate for further restoration activities, with a long-sought after restoration project identified by both SFN elders and our restoration biologists; removing upwards of 8,000 m3 of gravel that created a bar along the main stem of the Nanaimo River (remnant from historic industrial activity) and creating a new channel for freshwater to flow. The gravel bar has rerouted the majority of freshwater into the western section of the estuary, significantly reducing freshwater to the vast majority of the estuary, limiting salmon migration routes, and decreasing juvenile salmon rearing grounds.

Installation of the temporary clear span bridge and a before restoration look of the gravel bar

The fish window for this massive undertaking was relatively short, limiting us to just one month for in-stream work beginning in mid-July. However, our staff and project partners would be on-site daily for upwards of seven weeks, preparing the site and working out all the logistics of machine access, surveying in the proposed channel, installing a temporary bridge onto the gravel bar, collecting baseline water quality data, conducting bird nest surveys, removing invasive species, and a host of other tasks.

Taking baseline water quality measurements in the Nanaimo River Estuary

Additionally, with the high traffic along the only access road during the summer, it was decided that the rock pulled out of the gravel bar would be stockpiled in the upper estuary until the fall to minimize traffic to the local community. The gravel removal process produced over 800 truckloads of gravel to be stored, but thankfully, our friends at LaFarge Canada were happy to contribute to our project and will be moving the gravel in phases this fall to ensure minimal disruption to the local community.

Work days started early, kicking off with daily safety briefings before everyone started out on their assigned tasks. Fish salvages were conducted daily once the channel was beginning to take shape, as the overnight high tides would flood the new channel, leaving juvenile Salmon, Rainbow Trout, Stickleback, Sculpin and other fish species needing to be removed before work could begin.

Conducting fish salvage in the newly constructed channel before excavation work commences for the day

SFN, NTBC, and DFO staff conducting a fish salvage in the new channel

Once the nets were clear of fish for two sets, silt fences were installed to keep sediment from entering the river as the excavator worked, and a turbidity logger was installed downriver to monitor any changes to the water column.

Silt fences installed around the working excavators and a turbidity logger and multi-parameter water quality sonde monitoring for any changes to the water quality

As the weeks passed and the end of the fish window neared, the channel began to take shape, stretching approximately 330 m in length, 1.5 m deep and 14 m wide. Two riffles were built at either end of the channel to act as a grade control, with the upper riffle set to match an adjacent existing riffle and the downstream one to maintain water levels throughout the channel.

The excavator putting finishing touches to the lower riffle

Nearing completion of the channel, bulk bags were filled and transferred onto the site to create a coffer dam, separating the main river from the newly excavated channel. The bags were placed around the channel and reinforced with silt fencing, thus allowing the excavator to work in the channel to remove the final stretch of gravel and connect to the river.

The new channel nearing completion, with the coffer dam visible in the foreground

With the channel now complete, we will be continuing with our monitoring work in the estuary, including monthly water quality surveys, fish and wildlife surveys (i.e. bird and benthic invertebrates), and annually assessing flow through the new channel. We will also be moving toward the next phase of the project, which includes removing the stockpiled gravel, planting native species, and restoring the stockpile site.