Why are wetlands the smelly unsung heroes of B.C., and how can they be better protected? As efforts to preserve biodiversity and combat climate change intensify, wetlands have taken center stage. These dynamic landscapes play a crucial role in the ecosystem but can be challenging to understand and safeguard. It takes skilled and dedicated experts to analyze them—people like Brianna Powrie, an Ecosystem Biologist at The Nature Trust of BC.

“Wetlands are a lifeline for so many different species,” Brianna explains from her home base in Kamloops. “They provide everything—food, shelter, water, corridors for migration, and nesting and breeding habitats. For many species, wetlands are essential.”

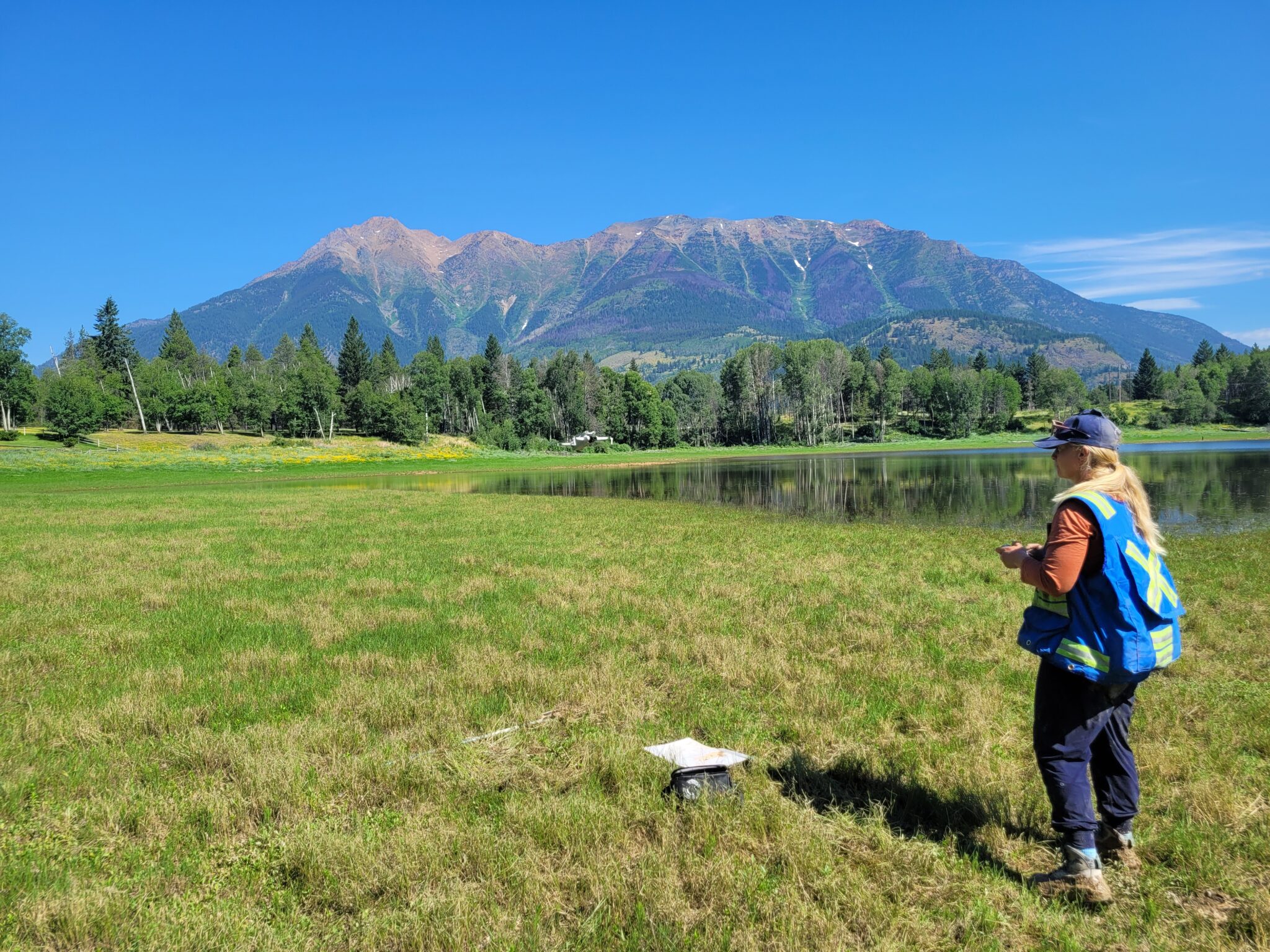

Over the past two field seasons, Brianna has been part of a federal initiative to map Canada’s wetlands, with a focus on those protected by The Nature Trust of BC. “There are many different kinds of wetlands,” she says. “Bogs, fens, and marshes are terms people use interchangeably, but to a biologist, they are distinct ecosystems that support different species and require specific conservation strategies.”

Brianna’s role involves assessing vegetation, soil composition, and hydrology to classify wetland zones. “We spend anywhere from one to four days at each site, depending on its size, complexity, and accessibility,” Brianna explains. “Plant species can help indicate the type of wetland. For example, plants that thrive in acidic or stagnant environments can help us identify bog wetlands. Relying on plants is important because these wetlands aren’t always wet—some are only saturated for a short period during the growing season. That’s why we need these other markers to identify the type of wetland.”

This data, including ground and drone photography, contributes to the most comprehensive and up-to-date wetland mapping in Canada. “With this information, organizations like The Nature Trust of BC can prioritize conservation efforts and identify key areas for restoration projects.”

Encounters in the Field

What is fieldwork in the wetlands like? “Being in the field, immersed in nature, and getting my hands dirty is my absolute favourite thing,” Brianna says. “Every day is different, and you never know what you might encounter.”

One unforgettable moment took place in the East Kootenay region. “I was in a wetland, head down, entering data on my tablet. I must have been incredibly quiet because when I looked up, a young badger had emerged from the trees. It walked through the mud, pausing now and then to dig. Then, to my amazement, it started moving toward me. I stood still, barely believing what I was seeing. Badgers are endangered in B.C. due to habitat loss from ranching and land development, so this was an extraordinary sighting. When it got about a meter away, I decided that was close enough and shifted slightly. The badger stopped, stared at me for a few seconds, then calmly made its way along the water’s edge, took a drink, and wandered back into the trees.”

American Badger

Protecting Wetlands

How can we all help preserve these vital ecosystems? “There are so many ways to support wetlands and nature,” Brianna says. “Donating to organizations like The Nature Trust of BC is a big one, but even small actions add up. Taking five minutes to sign petitions and write to your government representatives can have a huge collective impact. Even at home, you can plant native pollinator species—every little bit helps. There’s so much we can do, and a lot of joy to be found in reconnecting with the natural world.”

Do Wetlands Really Smell That Bad?

Brianna grins. “They often don’t smell great,” she admits. “There’s the sulphur scent, the stagnant water, and decomposing vegetation. But to me, it’s the smell of nature, and I kind of love it.”

![]() By Mark Sapwell, Communications Volunteer

By Mark Sapwell, Communications Volunteer